Localizing with Unity

I am currently sitting at home, polishing off work as my chicken broth simmers in the kitchen. It’s a nice way to start off my last Winter Break at MIIS. Having free time is an amazing feeling. I made two pizzas this week! They both turned out delicious, which is more than I can say at my attempts at digital pizza making with Teamkeen’s Pizzeria, a Unity asset and “almost finished project” that my team and I decided to localize for our final project in Max Troyer’s “Software and Games Localization” course. Luckily, you don’t necessarily have to be good at a game to be good at localizing one. In that respect, I think I can say I leveled up. Here’s a short run-down of what I learned.

Choosing Our Challenge

Throughout our semester studying software and games localization, we encountered a variety of challenging puzzles resulting from the sheer variety of platforms available to host our materials. Some of these platforms handle localization solutions more easily than others. Finding out how to solve each issue that arises is part of the puzzle-solving appeal of localizing this type of material. What it also highlights is how badly we need localizers in at the root of things, spearheading internationalization so all those best practices we like to see actually get implemented on a fundamental level.

That said, our team chose to work some more with Unity. It doesn’t have its own localization platform, which I feel is a loss, but we did have the opportunity to work with a very lovely alternative to built-in localization. The wonderful Inter Illusion team was gracious enough to allow our class to have access to I2 Localization, a quite frankly impressive Unity localization asset. We had had experience using it simplify our experiences hardcoding and using the toolset to softcode games, but we hadn’t had time to veer into the realm of images. That’s where our final project came in. Pizzeria’s UI was sufficiently complex and had enough localizable material on the loading screens and game play objects to ensure that our team would be reviewing the principles we had covered in class and opening up new layers of difficulty.

Organizing the Team

The next step was figuring out how to organize a team of three to handle this project. Given the amount of text we had to translate, we decided on a cloud-based approach. We opted out of using TMSs for the clean simplicity of a Google spreadsheet, shared between the team, whose members would serve as localizers and translators.

Since the messy world of coding would only be exacerbated by running different instances of the project on three computers, I took the onus of hosting the localization process on my computer, which meant that I had the most time available to fiddle with it as well.

Hardcoding and Softcoding

And fiddle I did. Organizing the workflow and editing processes was nothing. We were suprisingly effiient and my team was responsive. If I found hidden translatable material after my initial trawl through the game, the cloud-style organization of our team allowed for that material to get localized to Russian and Korean quickly.

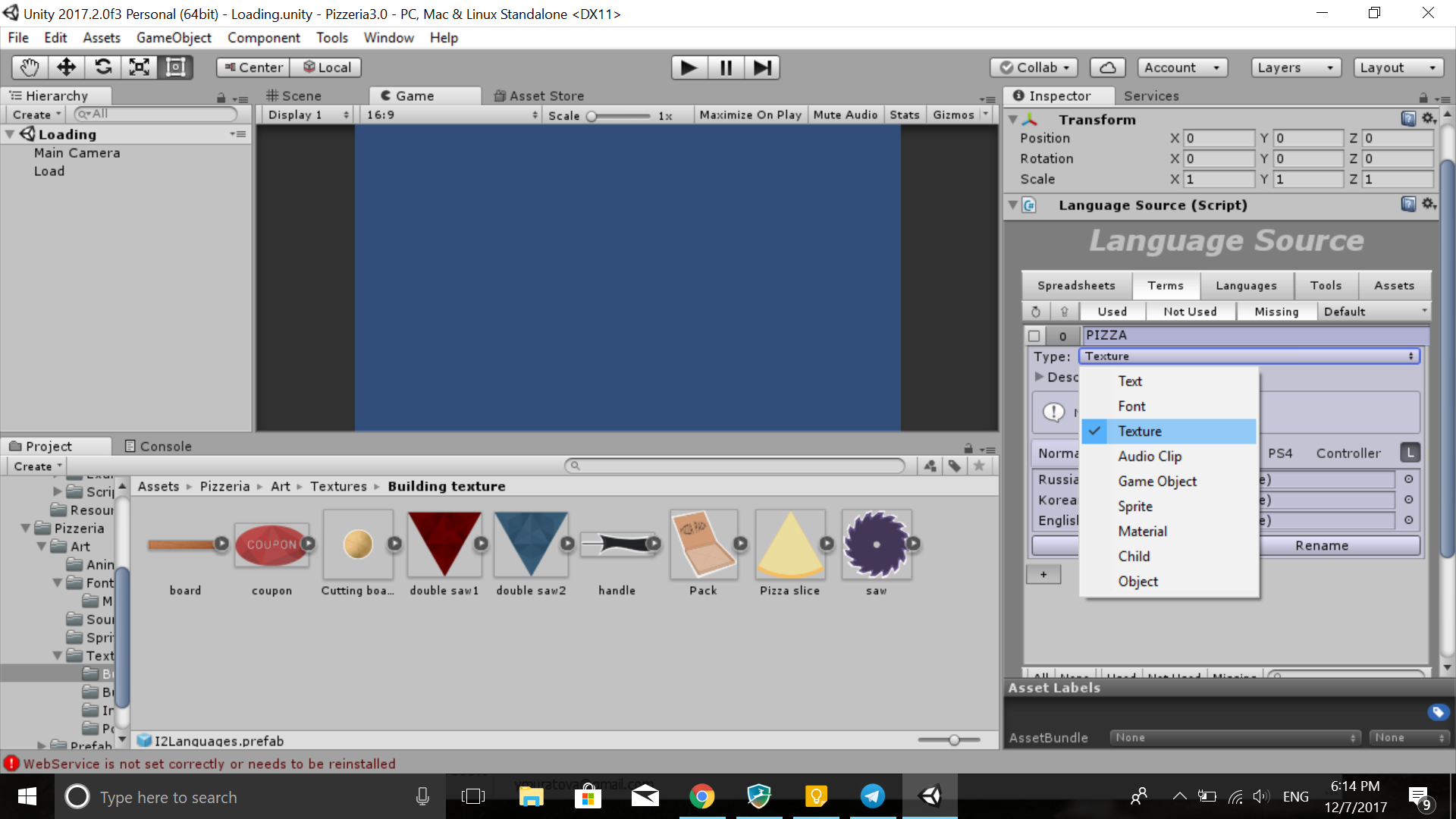

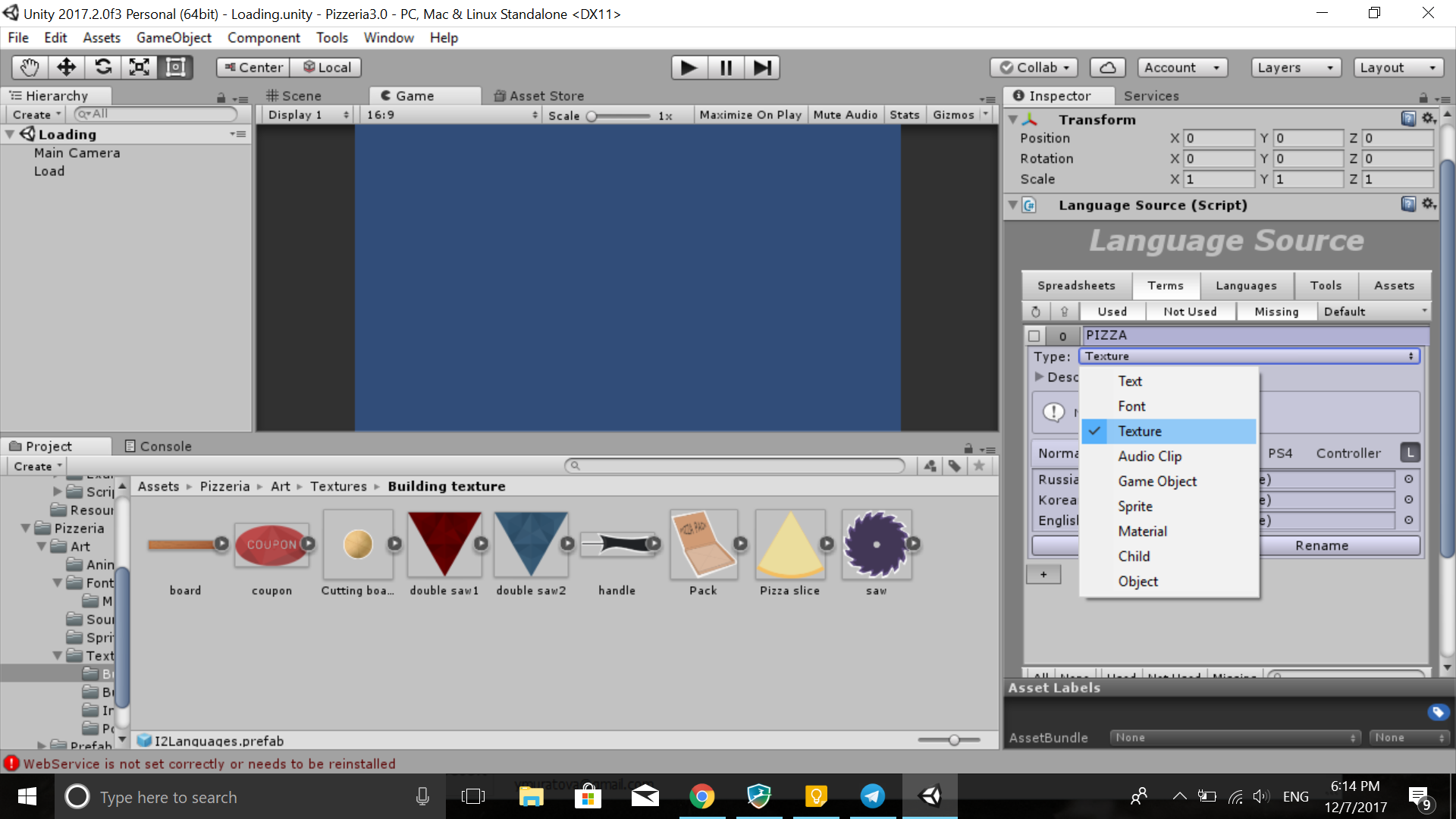

I2’s convenient interface made localizing images into multiple languages a snap.

I2’s convenient interface made localizing images into multiple languages a snap.

Really, the tough part was working within the structure of the game. It was a simple game, but oddly coded in some places. Various UI screens would have certain text hard coded and other text soft coded through the Unity interface. The former needed to be localized through hardcoded variables.

This inconsistency is normal, especially for a small game, so it was a helpful introduction to the kinds of problems that may arise. Game localization is clearly a field where you need to be able to run through things with a fine toothed comb, and, luckily, I learned that I have a few of those in my mental toolkit.

We managed to pull it off. The images were localized in gameplay and even match our localization buttons to the general theme of the game. That said, things weren’t always that easy to solve. In fact, some things couldn’t be solved the ‘Right Way’ at all.

Troubleshooting Gallery

Of course, much like any project that hasn’t been internationalized from the start, especially when that product is a piece of software, things are bound to go wrong. One such case was a loading screen that consisted of a .psd with text layers that was semi-hardcoded into the game. In other words, there was already a variable in the code of the game, three of them in fact, that pointed to the loading screen. Those variables could be altered in the Unity Interface, but because all three variables were in one component, I2 could not isolate the .psd to localize it. Now, I’m sure I could have figured out how to recode the game, but we were on a time crunch. So, we did the next best thing: we localized it by removing the text from the loading screen, letting the interface imply the loading on its own.

Now, while this isn’t the ending I would have liked, we were on a time crunch. Really, upon further reflection, we realized that sometimes, clients don’t want the best solution, they want the fastest or the easiest solution. Simple fixes are a valid solution and we conscientiously chose our solution. What mattered was that, in making that decision, we carefully weighed the costs and benefits of our options and we had a reasoning behind the choice we made.

Other issues, like the ones below, came from the fact that we were expanding and learning about the system. Learning to fix them taught me more about Unity and how to best approach the organization of a game localization project.

While the time I spent troubleshooting still ended up going over the estimated time we were each supposed to spend on a project, I still think it was worth it. Each fixed problem gave me more experience points, to leverage a gaming metaphor, and allowed me to level up in this field of localization.

The Final Product

Last but not least, I had the chance to watch what we had done, to see everything work smoothly, and that was what was really worth it. An archived version of the proof of concept for this project can be found through the Internet Archive.